The explosion of analytics in sports has brought with it a myriad of new statistics. Data Scientists continue to quantify performance with more precision and accuracy. Despite the development of new metrics, one statistic that has been around for over 40 years and is still incredibly popular is Greens in Regulation.

Is the Greens in Regulation (GIR) statistic old and out-dated, or does is still provide value in the world of Shotlink and GPS tools? Should the average player be using GIR to track improvement?

My last post described 7 characteristics of good golf statistics, in this post I will use this framework to evaluate how useful GIR is, and how it might be improved.

Definitions: What is GIR?

Greens in Regulation (GIR) has been around for so long because it is relatively straightforward to compute and use. A player is on the putting green in “regulation” if he or she has a putt for birdie (or better). This means that a successful green in regulation occurs when a player gets on the green in one shot for a par 3, two shots for a par 4, and 3 shots for a par 5. Typically the Greens in Regulation statistic is expressed as the fraction of holes in which a player successfully hits the green in regulation. For instance, if a player’s GIR is 35%, it means that 35% of his greens are hit in regulation (or 35% of the time he has a birdie putt).

Evaluating GIR

Now that we have a clear definition of GIR, we can evaluate its usefulness through the 7 characteristics I described previously. I will give GIR a score out of 5 for each criteria (except for relative/absolute, which is a categorial description).

Reliable: 4/5

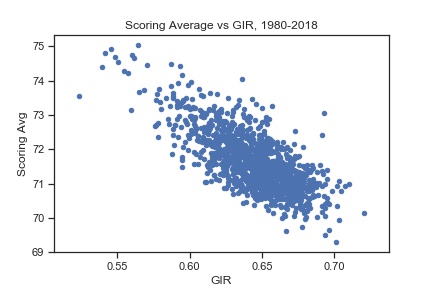

Greens in Regulation has dominated golf statistics for decades because it consistently correlates with scoring. The figure below plots scoring average vs GIR for all players from 1980 through 2018.

The plot shows a clear relationship between the two statistics – while there is some variability, scoring average generally decreases as GIR increases. Roughly speaking, a 4% improvement in GIR corresponds to a single stroke improvement in scoring average. Thus at the tour level we can say that, on average, an extra green hit corresponds to an extra stroke saved.

While there is a general trend in the plot of scoring average and GIR, there is still quite a bit of noise in the data, and it would be useful to say how strong the relationship between score and GIR really is. Statisticians will often do this using a quantity called . The value in this plot is 0.53, which means 53% of the variability in PGA Tour scoring average can be described by the GIR. In other words, about half of the difference between one player and another can be attributed to GIR, while half is due to other factors. This should make intuitive sense, since we know that there is more to golf than just hitting a green in 1,2, or 3 shots, yet getting on the green in regulation means avoiding sand, water, and other troubles that can lead to a high score.

53% may not seem like much, but it is actually quite large for such a complex sport! When you consider how many aspects of a round of golf are not accounted for in GIR, it is pretty impressive that one number can account for more than half of a player’s scoring average. Furthermore, the GIR statistic has been shown in a number of studies to correlate with scoring average across all abilities, not just on Tour.1

While nearly 40 years of data provide a clear correlation between GIR and scoring, there is some evidence that the correlation is slowly weakening. I will be discussing the evidence for this and the potential causes in an upcoming post.

Informative: 3/5

Greens in Regulation is a great way to characterize overall ball striking. While a green in regulation may be possible with just a chip shot on short par 4 or par 5, usually a GIR requires 1 to 3 full swings, and does not involve short game or putting abilities. Thus if two players have the same scoring average but different GIRs, we can say that the high GIR player is better at ball striking, while the low GIR player has a better short game.

While Greens in Regulation can tell us about overall ball striking, it leaves a lot of questions unanswered. Is a player with a high GIR successful because she has accurate irons or is she hitting longer drives that give her easier approaches? Is a player with low GIR playing too aggressively, poor at iron shots, or missing too many fairways? With GIR alone we can’t tell.

Predictive: 4/5

As described in the Reliable section, GIR correlates well with scoring average. Thus if I know a player’s GIR, I can make a reasonable estimate of his or her average score.

What we would like to know is not only whether we can explain how GIR relates to scoring average, but how well GIR can be used to predict scoring average. One way could be to look at new data as the PGA Tour season progresses, slowly comparing how well this relationship holds up this year. However we don’t want to wait a whole year to see how our predictions do, but we can use the data we have to do something similar.

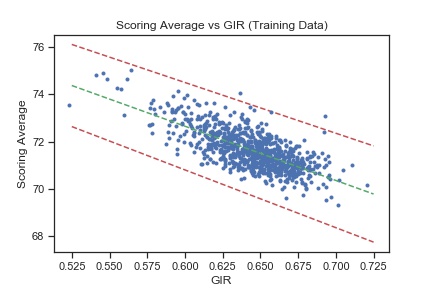

Data Scientists frequently test predictability by training their model with only a subset of the available data, then testing the model with the other (unseen) subset. The idea is that since the unseen subset of data has been chosen randomly, it can play the role that truly new results would play, and if the model is a good predictor of the unseen data we have, it should be good at predicting any future data we may obtain.

We can do the same thing with the simple linear relationship we saw above. Using data from 1980-2018, I withheld 25% of the tour players (chosen randomly) as test data, and fit a model with the remaining 75% (training data). The figure below shows the training data with the model’s fit plotted in green, along with the 95% confidence interval plotted in red:

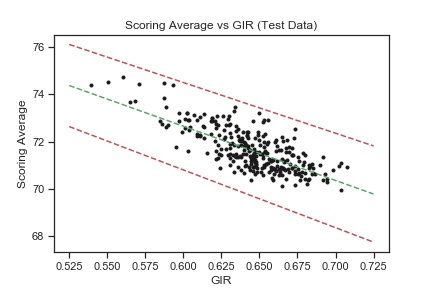

The next figure shows the same fit but with the test data superimposed:

Remember, those lines were computed without any knowledge of the test data, yet the test data still follow the fit pretty well and fall within the 95% confidence interval. Thus we found that we could use 75% of the data to “predict” the results of the remaining 25%, suggesting that the GIR is indeed predictive of scoring.

Applicable: 4/5

Greens in Regulation can be computed for any player at any level, making in very applicable. Indeed there have been a number of studies analyzing GIR performance across all player levels. Here is a plot from My Golf Spy showing GIR percentage for amateurs at different handicaps:

Regardless of your ability, tracking and improving your GIR can help you achieve your performance goals. Charts like this have led to the conventional wisdom, “4 greens to break 90, 8 greens to break 80.”

While GIR is applicable across a wide range of abilities, it is not particularly useful for those with very high handicaps. Players at these levels are averaging 2 greens or less per round, meaning there will be many rounds where they don’t hit any greens at all. At these low statistics, there will not be much difference in a player’s greens hit round to round, even if the player’s performance is varying a lot.

Similarly, GIR is not applicable when playing a course that is too long for your abilities. If you physically don’t have the length to hit a lot of the greens in regulation, your stats will be low regardless of your ball striking abilities.

A solution for either type of player is to change the definition of “regulation,” as I describe below.

Accessible: 5/5

Greens in Regulation is an incredibly easy stat for anyone to keep. By simply marking the greens hit on your scorecard, you can easily track your ball-striking performance for a given round, and by keeping those data in a spreadsheet or table, anyone can compute an average with common software. No need for any complicated tracking software, programming, skills, or teams of analysts.

Grounded: 2/5

The fundamentals of the golf swing tell us there are a number of similarities between full swings across all clubs in the bag, and since Greens in Regulation mostly incorporates full swing shots, we can gain some knowledge about our overall swing mechanics through the statistic.

However, GIR combines driving and approach shots, with no way to distinguish between the abilities of each. In addition, GIR provides no information about how close to the hole a player’s shot finishes or from where those shots were played.

In college I used to play against a player who hit his drives at least 50 yards past me. Many times we would hit the same number of greens in regulation. Who was the better ball striker? The answer is not straightforward and requires more information: was he hitting from the trees while I was in the fairway? Was he hitting his shots a lot closer while I was just barely on the green? Was he playing more aggressively because he had shorter shots? Was he so close that he could hit chips instead of full swings?

I think of GIR as a great starting point for understanding full-swing performance. If my GIR is high, I know my problems are probably with my short game – if it’s low, I know I need to work on my full swing. From there I look to more detailed stats to determine what exactly is the problem with my game.

Relative or Absolute: Absolute

Because GIR is computed without needing other players’ data, it is an absolute statistic. Remember that this characterization is neither good nor bad – rather it is informative on how it should be used.

While comparing your GIR stats to other players can help you determine whether you are above or below average, GIR can also help you understand your own game regardless of how you compare to others. If you are a player who hits a lot of greens, lag putting is probably more important to you for scoring. On the other hand, if you generally do not hit many greens, you probably rely more on your short game. Knowing this information can help you decide what skills you need to play your best, regardless of the game plan others use to score.

Overall: 4/5

Despite the limitations of a stat which combines several shot types, Greens in Regulation remains a benchmark stat for good reason. It is relatively easy to understand, compute, and use, and it strongly correlates with scoring. It is not great in explaining where ball striking problems occur, but it’s predictive qualities make it a great starting point when investigating one’s game.

Applying it: Modifications to fit your game

If you want to get better, tracking your Greens in Regulation is a must. It will tell you whether you ball striking is consistent for your abilities, and it can tell you how much you rely on your chipping or your lag putting.

There are also a number of steps we can take to improve on the standard GIR statistic:

Modify what “regulation” means to you

The standard definition of “regulation” means being on the green with a birdie putt. However, if you are a short hitter or a high handicap player, this definition means greens in regulation are rare for you. Why not instead make “regulation” mean having a putt for par? Chances are, if your scores are in the high 90s or 100s, you do not have many putts for birdie, and having a putt for par is not certain either. Tracking the times you have a putt for par as your personal “GIR” will tell you whether you successfully navigated the sand, water, and other troubles leading to the green, and will help you differentiate this part of your game from your chipping and putting skills.

Similarly, if you are a long hitter or a highly skilled player, there may be some par 5s or short par 4s where a green in regulation is almost a sure thing. In these cases where you have a chance at an eagle, putt, you may want to make “regulation” more stringent. When I play golf, I customize my definition of regulation for each hole based on how many shots I think it would take me to get on or around the green. With this technique I am able to better ensure that my GIR stats reflect my tee-to-green abilities.

Define “on the green” as having a normal putt

The standard GIR stat uses a nice, unambiguous definition of hitting the green: ball is resting on the putting surface. In reality, there is barely a difference between a ball that is one inch on the green and one that is one inch off the green on the fringe.

For this reason, I am generally not as stringent on what I count as a green in regulation. If I am hitting a relatively normal putt, I count it as hitting the green. I don’t count putts that are so far off the green that I need to account for the effect of the fringe – just those in which the only significant difference is that I don’t get to mark my ball.

Conversely, you may occasionally see a player on TV choosing to chip a ball that is technically on the green (either because of a steep slope or sharp turn in the green shape). Although this player technically is on the green, he still has to chip, thus removing the primary benefit of being on the putting surface. For this reason, I would not count that hole as a green in regulation. I also wouldn’t count a 100+ ft putt with lots of undulation – it seems more like a short game shot at that point.

Add a “Drive in Regulation” stat

The biggest challenge to GIR is the fact that it combines driving and iron play into one stat. To help me differentiate between the two, I keep track of what I call “Driving in Regulation,” which to me means hitting a drive that put me in a reasonable position to hit a green in regulation. This means the green is at a reachable distance and my ball is in the fairway, light rough, or a shallow bunker with an easy lie.

Keeping this stat does not differentiate between a long, straight drive giving me a wedge from the fairway and a short drive leaving me a long iron in the rough, so it cannot fully distinguish between the two skills. However, it does help me determine if I am properly putting my drives in play, or whether I am too errant to effectively advance the ball. If you want to know whether your accuracy off the tee is leading to trouble, this is a quick and easy way to find out.

Hopefully with these modifications you can take this simple stat and use it to fullest effect this season!